Company management meetings and site visits are integral to our investment process, and where possible, we look to visit core regions at least annually.

This was a unique trip given the mixed rhetoric we have been hearing on the region’s geopolitical and economic fronts relative to a very positive fundamental outlook for infrastructure operators. As always, it was invaluable to be in country comparing our regional outlooks and concerns (from an external lens) with the mood on the ground from locals and experts alike. It reinforced our thinking on regions, sectors and companies that looked interesting, and by contrast, where we had growing concerns.

Politics

The domestic and global political landscape is the single biggest headwind for the LatAm region at the moment. From US election policies and China’s potential retaliation to the global demand outlook and domestic policy shifts, the region has a strong mix of positive and negative catalysts. It’s incredibly relevant to the infrastructure outlook, and we spent a great deal of time exploring the theme over the two-week trip with those that have greater insight. As such, we have dedicated an entire piece to the political landscape in this two part Trip Insights article.

At the ground level, the mood across the region seemed content, if not relatively buoyant. This is clearly supported by the reigning populist governments who have significantly improved lower class living standards, supporting domestic consumption. Domestic politics were not top of mind or raised in conversation, but the US election was a near-term concern and conversation point.

Mexico

A big year for Mexico and one that has created near-term political uncertainty. While the June election win for the ruling Morena party candidate, Claudia Sheinbaum, was widely expected and priced into markets, what surprised was the degree of popularity and overall majority that she achieved. Domestically, many are still digesting the fact that she won by a landslide margin of over 33 points, receiving the highest number of votes ever recorded for a candidate in Mexican history, and importantly, more support than her ‘mentor’, departing president Andres Manual Lopex Obrador (AMLO)[1].

Structurally, it could be argued that the Mexican election system is flawed – the single (six-year) presidency certainly does not allow time to ‘settle into the role’ nor create any public oversight on electees looking for a second term. The one-and-done model can promote speed of execution, and for those with an ego looking to leave a populist ‘legacy’ ignores the longer-term fundamental checks and balances of economic policy. This is clear as AMLO departs:

- His 2018 cancellation of the partially constructed Mexico City Airport as per his election promises – this was a US$13bn project with a sunk cost for the government of ~$7-8bn. Further, it has cost the population an unquantified sum in lack of ongoing airport connectivity and efficiency.

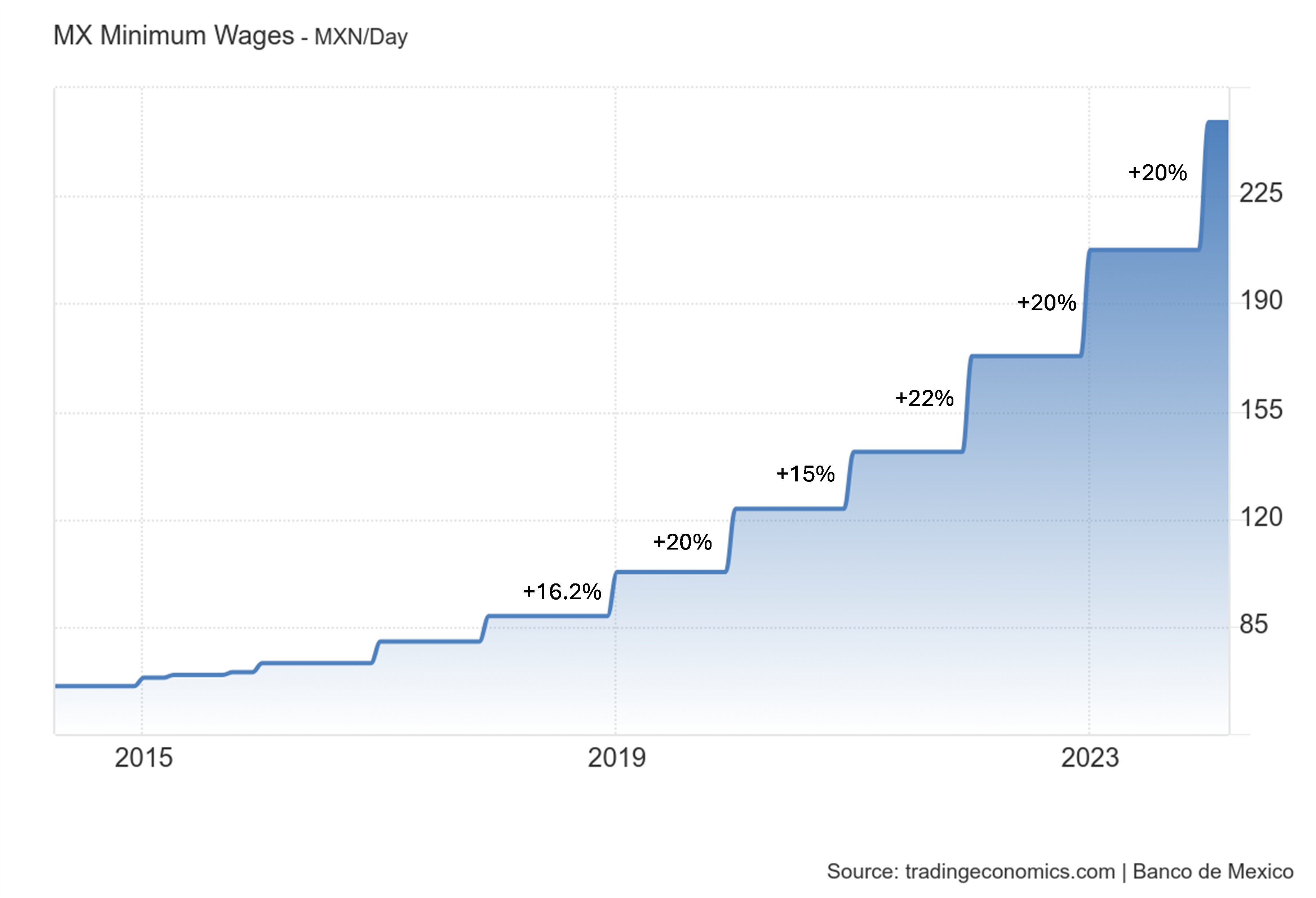

- Meteoric increase in minimum wage with annual increases of between 15-22% under the AMLO regime including +20% in 2024.

- National ownership of generation capacity, with AMLO advocating an energy sovereignty policy resulting in much-needed foreign investment leaving the country. As a result, energy security could delay Mexico’s near shoring potential.

These points will be discussed further in Economics in part 2.

Importantly, Mexico has survived AMLO’s mandate relatively unscathed for the moment, and on October 1, he will exit the arena, never to return. However, the incoming Sheinbaum does not have as easy a path with the government budget in significantly worse shape as a result of AMLO.

Over the medium term, the consensus view is Sheinbaum will prove to be more pragmatic than her mentor, having her own mind, policies and priorities to advance Mexico, particularly within the energy domain. Positively, given her popularity exceeded that of AMLO, there is no suggestion anymore that she is just his ‘puppet’ dancing to his tune.

However, in the short term, concerns are definitely elevated as the Morena Party has won a ‘super majority’, effectively removing the checks and balances of a less dominant government. Interestingly, while we were in Mexico, there was some argument that they would not achieve this majority. However, on August 23, the INE (National Electoral Institute) confirmed Morena’s position[2]. This is the single biggest near-term headwind for Mexico and the key concern of domestic specialists as this opens the door for the easier passing of controversial policies. As discussed, whilst widely believed Sheinbaum will be pragmatic and work within the need to attract international capital, in the short term, unpopular policies (at the international level) could be passed, with none more controversial than the electoral reform[3].

Electoral reform

During his term, AMLO looked to pass electoral reforms many times, and was successfully blocked at each attempt. The latest in February this year looked to restructure the INE[4] by reducing the number of counsellors and requiring that electoral judges be elected by popular vote. It further supported the elimination of all seats allocated by proportional representation, reducing the Chamber of Deputies by 40% from 500 to 300 and the Senate by half from 128 to 64 seats. The biggest concern is the election of judges, amid fears that this will corrupt the system.

AMLO would have loved to see this reform passed ahead of his departure. However, even with delays, Sheinbaum has stated that she will push forward with the reform and has additionally proposed a constitutional amendment to prevent re-election for any popularly elected position.

While we were in Mexico, the base case was that this reform would be passed and that this was largely priced into markets, with Mexico trading at approximately 11x forward earnings, which is more than a 25% discount to its historical average of 15x, or two standard deviations below. This level has only been previously reached during the pandemic, during the GFC, and toward the end of 2023 post the interference in the airport concessions.

The ongoing concern is how this reform translates into judicial resolve, with expectations that this will create increased market volatility until it had been tested over the coming six to 12 months. Passing the reform itself is no longer the issue – rather it’s waiting on the first test of the new system in the courts, with the timing on this very unclear. It could prove to be a storm in a teacup, or it could introduce electoral corruption and derail foreign capital flow to the country.

Recent timeline to the bill

- August 16 - the judicial reform bill was sent to the constitutional commissions in Congress to start the legislative discussion.

- August 21 – the judicial powers instigated a strike with a participation rate of ~85%.

- August 26 – the commissions approved the amended constitutional bill.

- First week of September – the bill was debated by the plenary of the congress, noting that there have been 100 amendments to the original judicial reform presented by AMLO in February 2024, but the core mandate to elect judges by popular vote remained intact.

The transit of this reform is a clear overhang for the country over the near to medium term, and must be factored into our country risk assessment. Importantly, while domestically this was also a disappointment, the rhetoric was not all doom and gloom, with expectations that processes and the need for foreign capital should provide fundamental system oversight. In particular, the market reaction to interference in the airport sector last year (discussed in detail in Part 2) gave the government and lawmakers some insight into what could happen if they did not uphold contracts and laws (the whole market was punished). At the same time, there was recognition that markets will be volatile in the nearer term.

Pros to Sheinbaum

Having focussed on the clear negatives of the current political dynamic, it’s only fair to highlight a couple of potential wins for Mexico that could be supported by the current regime:

- Near-shoring – a huge theme globally and Mexico is a clear beneficiary of the opportunity for near-shoring. This is receiving significant government support as they, and their neighbours, look to reduce exposure to China. The biggest hurdle to the return of commercial / industrial / manufacturing hubs is the security of energy supply. Importantly, both the exiting and the new government have recognised this and are working to reinforce energy positions and storage to support onshoring efforts. As this opportunity continues to grow, and the data centre opportunity also enters the mix, the government must address this or derail Mexico’s growth. This is something Sheinbaum is very cognisant of.

- Energy investment – as mentioned above AMLO had a strict energy sovereignty policy with an associated departure of significant foreign sector investment into the energy sector. However, Mexico needs foreign capital if they are in any way going to achieve energy security and support the near-shoring opportunity. Importantly, Sheinbaum has very clear and practical ideas on the need for diversity of source and increased investment in the sector. As such, it’s widely anticipated that policy will again shift to support and attract foreign sector capital.

- Social programs – the big populous win for AMLO has been an exponential growth in the minimum wage and social programs during his tenure at +20% p.a. While Sheinbaum is supportive of ongoing social mandates, she has been more targeted in new programs and more conservative in increases to existing programs at ‘above inflation’, which shows some economic discipline within government budgets that cannot continue to support AMLO levels of increase. Improved living conditions for lower class is also supportive of domestic consumption as well as a reduction in poverty-led crime and shadow economies.

- Security – improved security and reduced crime and violence were top of mind for voters, and important at an international level for investors and visitors alike. AMLO’s “hugs, not bullets” slogan has provided little comfort. By contrast, when head of government in Mexico City, Sheinbaum successfully introduced policies to bring homicides to a level not seen since 1989. She has committed to replicating this success at a national level. While this is not simple, it does not rely on social justice and should see more success and greater confidence that the government is working to address violence at all levels, attracting tourism and international businesses to the country.

As infrastructure investors, these are themes we can and would like to participate in, as would many foreign investors. Notwithstanding near-term concerns, we continue to see the risk/reward trade-off as attractive for key Mexican airport operators.

Brazil

After Mexico, the political situation in Brazil looked remarkably calm and stable. Reigning president Lula da Silva is a decisive character, loved domestically but ‘feared’ internationally due to his leftist rhetoric. But a clear takeaway from this trip is that it is largely rhetoric – he is noisy with his populous stance but pragmatic in his execution. And the biggest check to his response is the level of the Brazilian currency - if his policy weakens it too far, the masses suffer, which in turn means his popularity suffers. That is, the view on the ground is that while Lula will remain ‘noisy’ he listens to the FX and retracts when the BRL to USD weakens past R$5.50.

In terms of the political agenda, it’s very interlinked with the economic one. The key areas of discussion included:

- The upcoming appointment of a new chair of the Central Bank of Brazil and the transition thereto.

- Political adherence to fiscal constraints and how to cut spending/increase revenues to support spending.

- Inflation targets and policy commitment.

- Infrastructure and the ongoing privatisation of assets and projects to support national and state investment growth – this was an important discussion at a national level as well as on state-led panels.

- Next election and Lula’s potential competition.

We touch on each of these below.

Central bank replacement

In line with set terms of office, the current Chair of the Central Bank, Roberto Campos Neto, will be stepping aside later this year to be replaced by a Lula-appointed candidate. This caused some concern within markets, with Mr Campos Neto very highly regarded, having promoted monetary autonomy and independence of government directives. By contrast, Lula was very vocal in blaming the high borrowing costs, and in turn the Central Bank’s policy, for limiting faster domestic economic growth. Having heard Mr Campos Neto speak on global and domestic economic challenges, I can reiterate that he is a very impressive, market-centric Chair, leaving big shoes to fill.

Whilst in Brazil, the widely-anticipated Gabriel Galipolo was confirmed as the next Chair of Brazil’s Central Bank. He is a 42-year-old economist who was previously the second in command at the Finance Ministry. The markets were initially concerned that he lacked technical expertise and would bow to political pressure as opposed to maintaining true independent policy. However, economists are warming to him, and he is winning support as a strong successor to Campos Neto, particularly as he has the ear of Lula. Importantly, Campos Neto was very clear that he wants to work with the incoming Chair to ensure a smooth transition of responsibilities.

Lula, who has been publicly vocal about his frustration with the high interest rates, has recently softened his stance, stating to policy makers earlier in August, “if they need to hike interest rates, then they need to hike interest rates”. Clearly, this removes any initial test of independence for the incoming Chair, and could even suggest Lula is willing to listen to the rationale of his appointed Chair before creating unnecessary noise - the change in tone coincided with statements by Galipolo that a rate hike was on the table for September's monetary policy meeting due to continued elevated inflation risk. This shift has appeased investors and commentators for the immediate future with one commentator stating that Galipolo had shown ‘persuasive ability’ with the administration.

Cynically, the message may have been conveyed to Lula that they should hike now so that they can get inflation in check quickly. This should enable the easing of rates towards the end of 2025 or as Lula kicks off his 2026 election campaign, with sentiment turning in his favour as he campaigns into a declining rate environment and economic stability. Any delay to rate hikes could see forced increases into the campaign, which would not support his narrative.

Fiscal constraints

The adoption of fiscal rules has increased in popularity over the past 40-50 years, particularly in the emerging world. By regulating expenditure, debt, and fiscal outcomes, rule-based fiscal policy looks to limit political freedom with public money. Fiscal constraints are the bane of populist or left governments, as they restrict the spending required to retain the popular vote.

In Brazil, fiscal constraints evolved over a more-than 30-year period, and ultimately became very restrictive and untenable, with a three-phase limitation in place. However, these limitations were contradictory and ultimately resulted in a significant cut in public investment to support social policy, particularly through periods of crisis such as COVID.

With Lula returned to power in 2024, he proposed, and Congress approved, a new fiscal arrangement called the Sustainable Fiscal Regime (SFR) based on standard fiscal rules used in other countries, namely a revenue rule, an expenditure rule and a primary result target arranged in a particular fashion. It’s this new regime that currently guides budgets and is creating near-term controversy. We have outlined the new and old regime in greater detail in the appendix for those interested, but in summary, the new regime remains restrictive, promotes a surplus, is untested and subject to revision. Importantly it’s now causing Lula grief as he looks to adhere to his own policies yet supports social policies driving his popularity.

In June/July, the market was concerned that Lula was looking to ignore the very rules he had just introduced, and the market, and more importantly currency, reacted accordingly. In an effort to appease the finance minister pre-released elements of the 2025 budget and reiterated their commitment to the SFR regime. As such, the announcement of the 2025 budget in late August saw no big surprises. However, questions remain as to whether it’s achievable (this is discussed further in part 2).

Inflation targets

Historically, Brazil always had inflation targets or bands, but adherence thereto has been quite loose – a ‘close enough strategy’. An important shift on this trip was a firmer commitment to get inflation back to recently revised targets. This created some tension between the government and central bank, but a renewed joint goal to slow the rate of inflation is a strong market message and has been very well received by domestic market participants. As one strategist said, “stable inflation is core to global acceptance and maturity of the Brazilian economy”.

Privatisations

The depth and breadth of needed infrastructure investment again dominated discussions at a national and state level. A number of themes underpinned this investment trend, including:

- Core source of revenue for government budgets supporting social investment policies and the SFR.

- Investment as a driver of employment and ongoing economic growth.

- National decarbonisation goals – Brazil is hosting COP 30 in 2025 and is committed to showcasing the country’s resources and progress, with some interesting concessions coming to the market.

- Climate shifts – significant weather events across Brazil (as elsewhere) have further increased the need for infrastructure investment to strengthen networks.

- The potential of Brazil becoming a data centre hub and the energy/water needs to support this ideal.

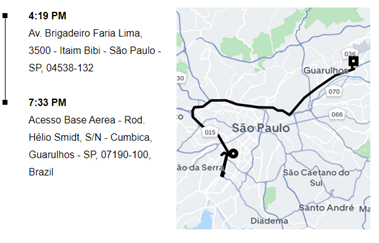

- Congestion issues and limitations caused by inefficiencies in the networks. As a personal example, my Uber trip from the centre of Sao Paulo to the international airport, a distance according to the app of 50kms, took 3hrs and 14min. There were no accidents or visible holdups, but rather normal afternoon congestion. Also of interest was that an Uber accepted this trip for a value of R$281 (A$74).

It should be noted that Lula remains noisy on the need for state-owned enterprises to remain in government hands and that their role goes beyond profitability to providing public services and contributing to national development. This ‘use for social good not shareholder value’ argument has been in play for decades, and has seen us rule out investment in certain assets whilst under government control – Eletrobras being the obvious example. However, we would reiterate that a lot of this is noise as the Lula government has auctioned/privatised more assets during its terms in power than any other government in recent history, for reasons discussed above.

Importantly, a key takeaway was that the opportunity to invest in attractive infrastructure assets in a growing and increasingly fiscally responsible market is enormous.

Next election

Although still two years away, there was a lot of discussion around the 2026 Brazilian presidential election, with market centric commentary quite positive on the potential for a shift to the right. While Lula’s popularity remains strong and he is eligible for a second term, it’s thought that the 2026 election could offer some of the best political competition in many years, with some very viable right candidates potentially coming into play including:

- Tarcisio de Freitas – current governor of Sao Paulo, was the Minister of Infrastructure under Bolsonaro.

- Eduardo Leite – current governor of Rio Grande do Sul. He is very young at just 39 years old, so probably more a 2030 story.

- Romeu Zema – current governor of Minas Gerais. He’s a businessman by background and a champion of privatisations.

I would err on the side of a Lula re-election, and am sure he will work tirelessly to retain the popular vote. However, a political shift would offer an unexpected country and market tailwind.

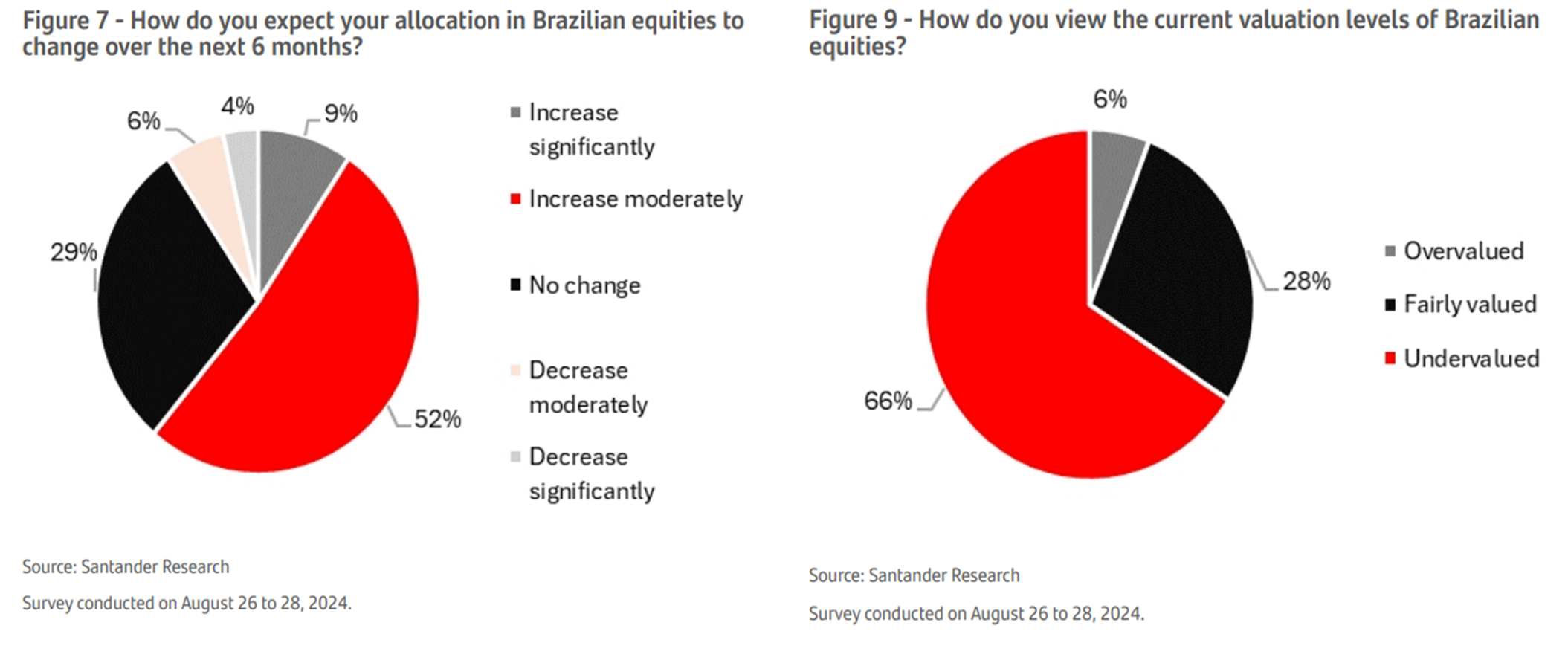

As an aside, among emerging markets investors, the LatAm region is currently overweight and with Mexico “dethroned” from the structural overweight, Brazil is gaining favour at a fundamental level and with the FED cycle perceived as a further tailwind for the country. As always, international investors are more positive than locals and driving flows into the market.

USA

Given its importance to the region as a neighbour and key trading partner, it’s impossible to visit Latin America and understand the mood on the ground without a discussion on the USA. This was never more apparent than this trip given the proximity of a hotly contested US presidential election with some polarising policies in play.

In Mexico, the focus was on a potential Trump victory and policies that could cause global and domestic concern, namely:

- US protectionism with Chinese and global tariffs – not a significant concern for Mexico and, in fact, could be an opportunity as the near-shoring opportunity ramps up. However, Mexico recognised that this could have global consequences which must be navigated – economically it’s inflationary, supply chains would be disrupted etc.

- Immigration – Trump has been very vocal yet again on the crack down to illegal immigration and borders. Domestically, they don’t have a problem with a stricter strategy, highlighting that they too are fighting the illegal immigration war.

- The war on drugs – surprisingly this is the policy that caused most concern domestically. It was widely viewed that any attempts by Trump to involve himself in the Mexican drug war would not be welcomed at a political or local level– the response was very much ‘control your demand and don’t blame the supply’.

By contrast, in Brazil, the outcome was far less directly relevant, with the focus more on the Fed move and how the outcome could change this trajectory. The head of the central bank commented that there are three recurring themes in the electoral debate with an inflationary basis:

- No sign of fiscal policy austerity.

- Immigration.

- US protectionism and increasing tariffs.

Argentina

While it was not a stop on this trip, Argentina certainly was a topic of conversation given the recent radical shift in government with far-right economist, Javier Milei, now in power and executing on election promises.

Milei was very vocal in the need for swift, sharp action with associated short-term national pain. He immediately started executing on an extensive plan to overcome years of economic and political mismanagement. In a very short period of time, he managed to:

- devalue Argentina’s currency by 50%;

- slash state subsidies for fuel;

- significantly reduce government positions; and

- cut public spending.

This has seen a shift from a fiscal deficit in December 2023 to a surplus in April 2024 and has resulted in a sharp contraction to the Argentinean economy as consumer spending is drastically cut. However, his number one target remains inflation and while it has slowed MoM and is now below double digit (+4% in July and +4.2% in August), annualised measures still have a very long way to go. Importantly though, the discussion has shifted to the last mile as opposed to hyperinflation.

While there have been some near-term successes, Milei is handcuffed by a lack of majority in congress and the need to strike deals to execute. This has seen much-needed asset privatisations and economic measures stall. Positively, he is looking to privatise over 20 state owned enterprises including the national water utility, railways, airlines and the postal service. However, his omnibus bill, which includes these privatisations and a number of other economic measures, was defeated for a second time in February and the party is working to re-package these into smaller digestible pieces.

Milei is also facing a lot of backlash from the unions and workers as their spending power deteriorates, which is creating a geopolitical noise and social unrest.

Argentina remains ‘red’ within the 4D country risk assessment and as such is uninvestable at the moment. However, time in seat and ongoing execution by the current Milei- led government could certainly see an upgrade in the future. It feels like he is turning the ship but that it will be a very slow shift. It’s a country steeped in history and wealth, and would like nothing more than to see political stability leading to economic recovery and the ability to participate in the huge scale of infrastructure investment needed to return it to the powerhouse it once was. For now, it’s a ‘watch and wait’, but we’re slightly hopeful that Argentina’s time could be coming.

To be continued...

In the second instalment of this Trip Insights, we explore the economics of LatAm and discuss the key infrastructure dynamics and drivers of our portfolio positioning in the region.

To view the appendix, download the article below.

[2] INE confirmed that Morena had achieved 364 seats in the lower chamber (obtaining a qualified majority) and 83 in the upper chamber (just three seats short of a qualified majority), and despite injunctions this decision has been upheld.

[3] September sees a transition month where AMLO will look to achieve an exit legacy. Sheinbaum takes office on 1 October, however, the party majority is in place throughout September with AMLO at the helm. While there is little he can achieve in one month, he has thrown all his support behind his controversial electoral reform as discussed below. Sheinbaum has supported the policy, which many believe is a ‘thank you gift’ to her mentor.

[4] The INE is an autonomous public agency responsible for organizing Federal elections in Mexico, that is, those related to the election of the President of the United Mexican States, the members of the Congress of the Union as well as elections of authorities and representatives at local and state levels